SEVERAL DAYS AGO I woke up to a notice from WordPress, the outfit that hosts my blog, that someone had left a comment on one of my posts. Given that my blog attracts very little traffic, and that I hadn’t posted anything in days, I was naturally curious about the comment, so I quickly logged on and read the following, at the bottom of a blog I had written in May of 2015, about my high school days:

“What ever happen to Kathy Brisco, I am looking for a Kathy Brisco from crystal city from the year 1960 To 1964,,,,A friend of mine John Brannon is searching for her, text me at xxxx. Thanks Lillian”

At first I was bewildered by the question. Why would anyone believe that I had any idea where this person was? But then I remembered that in that post, I had written about my most memorable moment at Crystal City High School.

This is what I wrote:

Kathye Briscoe, Crystal City High School yearbook, 1964

If I had to pick a most memorable moment of my high school years, it would have to be that early Friday afternoon in November — during my sophomore year — when I was walking down the hallway that connected the auditorium and the main hallway. Our lunch hour had ended and we were all heading back to our classes. In the middle of that hallway I saw Kathy Briscoe heading in the opposite direction, with tears in her eyes.

“They shot him,” she said.

They cancelled classes a few minutes after that.

It was clear that this Lillian person had done a Google search on “Kathy Brisco” and “Crystal City High School,” and that the search engine had given her my blog post.

Why she thought I might know the whereabouts of Kathye Briscoe (the correct spelling of her name, I was to find out from my sister’s high school yearbook) was beyond me. I had known Kathye. She was a classmate and we had a number of classes together. I’m sure that during her three years at CCHS we exchanged many words, but I doubt we ever had a serious conversation about anything. We definitely weren’t friends. In those days there was almost no socializing between the Anglo and Mexican kids, and even if there had been, I was definitely not the kind of guy with whom a girl such as her would want to spend too much time.

Tommy Brannan, CCHS yearbook, 1964

Kathye was a popular, intelligent and attractive olive-skinned girl, always smiling. I don’t think I ever heard her say a cross word to anyone. Her family moved to town during our freshman year, when her father became manager of the local JC Penney store. They lived in a modest house on East Crockett Street, next door to the big house occupied by the local banker.

Soon after arriving, Kathye and Tommy Brannan became an item. Tommy was the son of a local schoolteacher and he was a year ahead of us in school. He was a jock, a star in football and baseball, and maybe even basketball. He and his best friend, Bob Taylor, the son a local lawyer, were Big Men on Campus. Loud. Boisterous.

Tommy and Kathye seemed like an odd, unlikely pair to me. She was refined, diplomatic and courteous. She didn’t seem to relish being the center of attention. He loved it. As unlikely as it seemed, however, the relationship thrived and I think everyone assumed the two would end up getting married. Then, at the end of our junior year, Kathye’s father was transferred to another store in another town and Tommy went off to try to be a college jock and that relationship ended. I never saw or heard of Kathye again.

AND THAT’S WHAT I told Lillian, in my email responding to her comment on my blog post: I had no idea where Kathye was and I doubted I could find her if I tried.

I thought that would be the end of that, but the next morning there was another notice of another comment on the blog post, this one from “John Brannon”:

“How can I find Kathy Briscoe, I am a friend of hers and I am very ill. I just want to thank her before I get to where I pass away thanks,,I live in SeguinTexas”

Now that got my attention!

I was pretty sure it was Tommy Brannan. I remembered, from reading my hometown weekly newspaper in years past, that he had moved to Seguin, gone into business and started a family there, and I thought I remembered that his name was John Thomas Brannan. So that all made sense.

But why would he misspell his own last name?

It then occurred to me that perhaps Tommy was too ill to write on his own, that maybe somebody else – Lillian, perhaps? – was doing the writing for him.

I posted this response:

“John, I really, really wish I could help you, but I have absolutely no idea where Kathy might be. I am sorry that you are ill and I truly wish I could help find Kathy for you. Unfortunately, my blog posts rarely have more than 100 readers, if that many. I know you call yourself John, but I think I may be right that you went by Tommy in high school. Is that correct? You were a year ahead of me in high school. I doubt you’d remember me; there’s no reason for you to. But I remember you. I hope you do find Kathy. I can’t say she was my friend, but we were classmates and were in several classes together. I have nothing but fond memories of her.”

WITH THAT, I thought I had gracefully excused myself from any more involvement in this intriguing and sad tale. I had asked myself what obligation I had to help this man from long ago, who had been briefly in my life but never a part of it. He was a stranger, really.

It is no secret that I have strong negative views about growing up in South Texas at a time when the small Anglo minority had all the power and treated us as second-class citizens, or worse. Tommy was very much part of that establishment.

Further, I had checked with my sister Carmen, who had been his classmate, and not only did she have no fond memories of him, she had one very nasty recollection: As a child, she was walking past Tommy’s house one day and he had come out on his front yard from where he started throwing rocks at her. And he laughed as she dodged and ran.

I wanted my response to his comment to be my last involvement in this matter. I really did. But two things prevented me from doing so. The first was that this guy – John, Tommy – claimed to be dying and he needed help on something he felt was important to him. There may not be a warm place in my heart for some people, but that heart – this heart – is not a cold heart. Didn’t I have an obligation to try to help another human being in need if I could?

The second thing was that my reporter instincts had kicked in. I had been presented with a challenge, an assignment, if you will, and I felt a need to pursue it, to try to find the answer to the question, “Whatever happened to Kathy Briscoe?”

SO I BEGAN the search, using the two web instruments I am most familiar with, Google and Facebook. They turned up nothing. I had reached a dead-end almost before I started. There are lots of Kathy Briscoes on FB, but not the one I was looking for.

But then I asked my niece to go to Carmen’s yearbook and take a picture of both Kathy’s and Tommy’s class photos. When I got them, I noticed that there was an “e” at the end of Kathy. It was Kathye, not Kathy.

Back to Google I went. It took a while, but I learned that she probably lived in Raymondville, north of Harlingen, and that her last name is now Austin – and that her husband had died several years ago. I learned that one of her sons had married a girl from Montgomery not long ago. But I couldn’t locate a phone number for her (even though a while ago I tried to replicate my search and came up with a phone number right away; go figure!).

I returned to Facebook and learned that even though she is not a FB member, she has friends who are, and some of them mentioned her. There was one post of a group of friends driving from Raymondville to Houston to see the opera Carmen, praising Kathye for her driving skills. Others mentioned going to the movies with her in Harlingen, and there was a picture of a group of women at a dinner, posing for the camera. There, near the middle of the back row stood a woman who looked very much like Kathye. She was also mentioned by the Raymondville Methodist Church’s pastor. In one of his posts, he asked for prayers for Kathye and her family as they prepared to remove her husband from life support. I called the church but no one picked up the phone.

I clicked on the church’s page and found more photos featuring her in the choir and other church activities. The photos left no doubt: this was the Kathye Briscoe I remembered. But I still didn’t have any contact information for her.

Meanwhile, while waiting to figure out how to proceed on that end, I did a Google search on Tommy. I learned that in addition to owning a pharmacy, he was in real estate, selling and buying ranch and hunting properties, and that he was involved in local politics. There was a letter he had submitted to the local commissioners court asking to be appointed to fill a vacancy on the court, and there was a story about his running for county judge in the GOP primary, pledging to run the county like a business. I also found an obituary for his mother, who is buried in Crystal City.

Tommy had included his phone number in the news story in which he announced his candidacy and I decided to try it. It was not an easy decision. For all I knew, Tommy was on his deathbed, barely able to move or talk, and the last thing he or his family needed was someone calling to tell give him information about an old girlfriend.

All this brought back memories of all the times that, as a reporter, I had to call grieving families to get a comments or information for articles I was writing. I hated doing it and I put it off as long as I could but in the end I called because I had to.

I DIALED THE number but there was no answer. Instead there was a message, recorded by Tommy’s unmistakable voice, saying nobody was home but to please leave a message. I did, telling him that I was pretty sure I knew where Kathye was but that I had been unable to get her phone number. I left my phone number if he wanted to call me back.

He did, identifying himself not as John but as Tommy, and sounding very much like the good old boy I remembered. And, to my relief, he sounded healthy. Or, if not healthy, certainly not like a man on his deathbed. We talked about high school and about people we knew. He admitted he didn’t remember me and I replied that there was no reason for him to: he was a jock and I wasn’t and we never had any classes together and we certainly didn’t socialize. He talked about his dreams about becoming a college and pro athlete, and about how those dreams were shattered when he discovered that at the college level, you have to be better than good to succeed.

“You think you’re going to make it because you’re good in high school – I was a big fish in a little pond – but you quickly learn that everybody is good at the college level,” he said. “And at the pro level, everybody is special.”

The conversation got around to Kathye and why he was looking for her. He explained that he’s been spending a lot of time trying to reach out to as many people who have been part of his life as he can, to let them know how much he appreciates their friendship. He’d talked to a lot of people, “but Kathye kind of just disappeared. Nobody seems to know where she went.”

He didn’t tell me how close he is to death and I didn’t ask. He thanked me for my efforts. I mumble some words about how sorry I was about his health, and before I hung up I gave him the Methodist Church’s number.

NOW IT WAS back to finding Kathye. I went back to FB and sent text messages to each of the friends who had mentioned Kathye in one of their posts. I told them who I was and why I needed to speak with Kathye. I didn’t mention Tommy’s health because it somehow didn’t seem right, but I tried to make it seem as urgent as possible, while going out of my way to not sound like some sort of stalker. I didn’t ask for her phone number or e-mail address, but I listed mine and asked them to ask Kathye to call me.

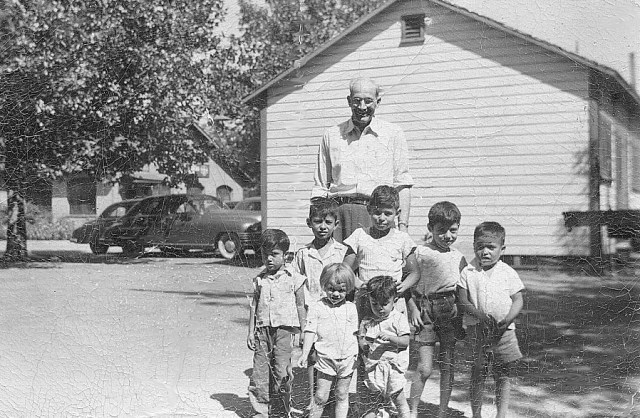

CCHS Band picture. That’s me, bottom left, and Kathye Briscoe is above me in the white drum major uniform.

“I don’t know if she’ll remember me, but if she does, it’ll probably be as Johnny or John, which is what I was called back them,” I wrote. “Tell her I played oboe in band.” Kathye was also in band and she played the bass clarinet, which meant she sat close to me in the wind section. She was the drum major for the band, and in a yearbook photo my niece sent me of the band, she stands out in her white drum major outfit in a sea of dark-colored uniforms.

I didn’t get any immediate responses but I knew that my text messages had been read because I looked at the statistics page of my blog and saw a quick uptick in the number of readers of that particular post that day.

After about an hour, I got a reply from one of her friends who said that, yes, indeed, I had the right Kathye. She always talked a lot about her years in Crystal City. Kathye would call me that evening, she promised.

Sure enough, about five o’clock my phone rang and I noticed that it was a Harlingen number. I picked it up.

“Johnny?”

Her voice sounded just as I remembered it. After all these years, how is it possible to remember the voice of a person who was never even that close to you?

“Of course I remember you,” she said, mentioning some of the classes we took together, and band.

She said she hadn’t spoken to anyone from her Crystal City days in a long time, except for one time several years ago, at a social function in Waco, when she overheard someone talking about Tommy and Susan Brannon of Seguin, and about Tommy’s illness. It turned out to be a classmate of Tommy’s.

“My God, that is the man I was supposed to marry!” she recalled telling herself.

We talked a bit about her years in Crystal City, about where she moved to after she left (San Antonio), and about people we remembered. She also talked about her family and life in Raymondville.

She wasn’t surprised when I told her why I was looking for her, about Tommy’s need to reach out to her. She said she would call him, and I gave her his phone number. I asked her if she would call me back after she did to tell me about the conversation and she promised she would.

She hasn’t. It’s been only three days but I really doubt she’ll call, and I can’t say that I blame her. Whatever conversation she had with her ex-boyfriend, it can’t possibly be easy to talk about.

I COULD CALL her back, or I could call Tommy, but I won’t. The thing is, I’m no longer a reporter and I don’t have to. I’ve done my job and this is where I have chosen to place my reporter instincts on hold.

I hope Tommy is able to talk to Kathy – and to all those in his past he has been trying to locate – and I hope he has found peace or whatever else he is looking for by reaching out.

And if a conversation between these two former high school sweethearts did take place, it’s their conversation, and that’s how it should stay. I don’t have to know.